Over the last decade I have been redesigning my life to do work that is meaningful to me. I did it by experiment. I tried many things, and deleted, erased stuff that didn’t fit. With no remorse but with trepidation. It costed me almost everything that society prizes.

Recently, I found what I was meant to do. Not a job. A vocation. A craft. I didn’t know if I was going to be good, or great, let alone the best at it. But all different parts of me joined in a choir, rather than have an argument. And that was good enough, and a relief. At last I had landed in a place I wanted no escape from. I was not expecting that the place would be quarantined.

After a few years working with executives there, I had started teaching the MBAs at the business school I graduated from 13 years ago. If you think that it is a privilege, you are right. It’s also a challenge, a delight, an honour.

But all those labels came stapled over activities that seem to have changed suddenly and thrown into uncertainty by COVID-19.

Except, maybe, my class.

Three weeks ago was the first in which INSEAD taught all MBA courses fully online. This included the one I had been looking forward to, and had just started to teach, in a physical classroom. It’s called Psychological Issues in Management, and it is not the kind of course you expect to take online. It is built on the premise that leadership is not just about your skills and tactics, but also about who you are and what you mean to others. People who take it want to learn more about themselves, and get to know their classmates better, and the course is designed for that, highly interactive, each session moving from concepts into experiential work.

None of the professors who have taught it before me ever, in their wildest dreams, thought of providing it virtually. And neither did I. Why put another (digital) barrier between us, when we are trying to remove those of our projections, presumptions, and dearly held theories? That is until the coronavirus put our assumptions about digital barriers to test.

Zooming in

My class was on the first day teaching resumed after France went on lockdown. It wasn’t the first time we would be teaching online, but it was the first time I moved a course online that was not intended to happen there at all.

I spent the days prior testing the best technological setup. It’s easy to get your head lost in the kaleidoscope of digital options, I found. How to moderate the chat? How to create breakout rooms? How does a virtual whiteboard work?

But after a while I realised that the transition to a virtual class didn’t really create new questions. It just amplified the ones that we always have to ask as educators: is the class and the course providing people with an opportunity to develop? Is this something that people will engage with, and relate to? Or just another transaction to complete, a gate to pass, in the sausage factory of “talent”?

The conversation about technology was a decoy. The important questions were about pedagogy.

Teaching in a Crisis

I reached out to everyone I could, especially my teaching coach, and other faculty who have taught this course before. What would they think about, and do? Of course none of them has ever been in a situation like this, which freed me up. As I engaged with them, through the very technology I would be using to teach, it started to dawn on me that we are in a different world now… we were all in our own homes, dealign with the lockdown, and figuring out how to work and live in these new circumstances. We were increasingly aware of our physical isolation which was bringing some of us closer together, and some of us farther apart.

There was something else brewing underneath all that digital ocean we now had to swim in. And in order to get in touch with that, I realised that amidst what looks like radical disruption, there are some things that can’t or shouldn’t change. The first one is that we have a task to do: to teach and to learn. Being a teacher starts with paying attention to what is going on with the students, yourself, and with the world. What was going on was not only the shift to teaching online — that was just a result, or shall we say: a very mild symptom of history in the making.

What was really going on was a human crisis that nations’ leaders all around the world have described as the biggest threat that they had ever faced. Angela Merkel framed it as a historical challenge bigger than that of unification of Germany, and French president Macron invoked war multiple times. (Trump, at first, called it a hoax). All by the way, examples of how leader’s identities are highlighted in crises, another learning point not to be lost for the class. They were also all asking us, some with conviction some with reluctance, to isolate and to stay at home to slow the spread of the virus, and give the national health systems space.

“What better circumstances to learn and teach leadership than in the middle of crisis that impacts us at such scale?”, I thought.

Upon realising what seemed to be obvious, I decided to go with the minimal setup: Zoom and Google Docs — and focus on the crisis that was unfolding around us as a backdrop. No fancy whiteboards, styluses, double iPad setups, or virtual backgrounds. Just me, at my home, separated by a wall from my home-schooled children and my wife who is now turning into a school principal on top of her many hats she has to wear, while I figure out how to make sure that the world that is changing in front of our eyes is studied and engaged with, rather than denied its impact on us. Doing so would rob us of an opportunity. In a way, I didn’t think teaching PIM has ever been more real than under the onslaught of a pandemic. When else are we going to have a better chance to learn and observe ourselves, and our leaders. When else are we going to learn then in the middle of crisis?

“We are not just meeting in a different space, we are meeting in a different world.” — I felt freed up again by starting my class by acknowledging the truth. And even more so by making room for students immediately after to speak about their experiences of what is going on. INSEAD MBAs come from all over the world. They make their home for a period of one year in a beautiful part of France, south of Paris, or in Singapore. This week however, that dream has turned into a surreal reality. We all were in circumstances that we have not necessarily signed up for. But I didn’t want to deny them the opportunity to express their lived experience of this event, and so I invited them to revisit the contract that we had crafted into at the beginning of the course, when we still had the chance to meet face to face.

I was hoping to model decent leadership in a situation like this. I wanted to avoid two mistakes groups can make when facing a crisis:

The first is to buy into denial. It’s seductive, because it buys us serenity, for a short while, but it can cost us everything.

The second is catastrophism, i.e. succumbing to the narrative that the circumstances has changed for the worse and there’s nothing we can do. This is more than a defence mechanism. It’s an abdication of responsibility, or rather of agency. We become neither leaders nor followers, then. We become mindless.

But besides avoiding these mistakes, there’s something else to be done in crisis first: and that is to make space for our whole selves and observing our experiences. Before we can engage in any new tasks, we need to get in touch with the feelings and thoughts, arising from the traumatic events and process them, together. Only once that is done, we can make space for the new.

Alone Together Uncertain Forever

Students filled that frame with their expectation and concerns, once again, as they had done in the beginning of the course. Their expressions were meaningful, heartfelt, and remain confidential. But one theme came up in that moment that spoke to my experience standing, or rather sitting, in front of that new classroom. The theme of isolation and resulting solitude. It is as if the lockdowns all around the world are surfacing feelings that are vaguely familiar, in organisations, but often buried under the routines of the boundary-less business world.

What I thought initially was going to be a study of crisis, was turning into study and experience of separation and loneliness that actually seemed to have existed before the quarantine.

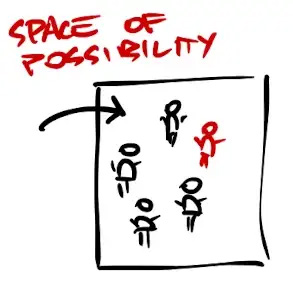

I realised at that point that learning about each other and ourselves is not enabled or disabled by technology, but by our own capacity to hold and be held: what we do as teachers, just as leaders, is to provide a space.

Leaders create and hold a space, where a story can be enacted.

It starts with people gaining trust that they will be seen as they are by the other; the teacher and their peers. Where we can cry and laugh, kick and scream, mourn and rejoice, resign and re-engage, and where others bear witness to our humanity. That safe space is necessary for us to accept what comes next in learning — the challenge that’s born out of people that care for who you can become, rather than who you are now. Once we know that we will be held in such regard, we can trust to be challenged and to challenge. And in such way a space for learning is created, a community, where people can reach their potential, where we can develop. That’s not just about learning new skills — that’s about growing our capacity for new and often uncertain. And that’s how we live in uncertainty: not with ready-made answers for all eventualities, but amongst people who hold us, and whom we can hold.

This quarantine and resulting isolation is pointing out that maybe we had been much more distant to each other than we thought, as now we are finding out: who is there that is holding us, and who relies on us to hold them?

Perhaps our hesitation to bring technology into the classroom was based on an assumption that somehow we can be closer to each other when we see each other in person. That proximity of our bodies is what’s necessary to fully encounter each other. This theory is based on a premise that we are more present when we are there physically with each other. And that’s not very different to the assumptions in the corporate world: working from home is still a novel idea for many workplaces, and in many it’s something that is met with reluctance.

But when we were there in person, did we actually feel more connected? Did we actually feel that we were not isolated? If anything, I was realising that Covid is serving a sobering lesson to those of us that are fortunate enough to be able to continue working: the isolation that we now frantically try to reduce with Zoom, is the reality that is somewhat familiar, but rarely acknowledged. That we were lonely at work in the first place.

Violent Politeness is the real plague.

It’s only been couple of weeks, but I can already say that I miss seeing students in their full form without the virtual backgrounds, and in their physical presence. The energy of the amphi, the potential between the different characters, the interaction between the subtle cues that people can’t hide, the staccato of excited minds, and the squeaky surprised silences. As well as the confused, doubtful, disengaged, unimpressed and bored. All that is often lost in the virtual projection, or perhaps I haven’t learned to read the virtual room yet. Time will tell. Either way, for now I count on the creativity of my students and mine, as we find the language that fits the new form. Thus far the students don’t fail to find ways to show all of the above, in new and surprising ways. It is good to see that we can always, as humans, find ways to annoy and to love each other, even in a lockdown.

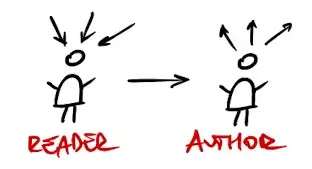

But Zoom will not replace an amphi. Hopefully it will make it better and different, if we continue to learn from all this. Perhaps it will teach us that real loneliness is not born out of separation, nor technology. It is born out of a belief that other people’s bodies or emotions can fill the void of our quarantined hearts that have not practiced reaching out, showing up, and beating to their own rhythm. We are never lonely when we make our own song. And we are never solitary when we are generous with each other, even when isolated. For that you don’t need zoom nor a classroom, what you need is courage and faith that you can author your own story, with others.

Who is the (co)author of your story?

The second session that week opened up with one of the students holding a baby on his lap. It does not happen often in the INSEAD classroom, not for a whole session anyway. Maybe times are changing after all, and the digital classroom is the future, and here to stay in some form or another. It would not have happened if not for this string of events. I will forever hold that image as a reminder that what really makes a classroom is our attention, and what we bring to it. Not the technology that (dis)connects us.

Big ♥️ to Amy, Gianpiero, Jen, @apeshkam, Derek, Amer, Sujin, The System, Noah, and others who held me — we never teach and learn alone.